Hope, Okinawa, Crisis Response

Crisis Response and Hopology

Over the past year, I have participated in a project called "Social Sciences for Crisis Response (Crisis Response Studies)," which involves the entire Institute of Social Sciences at the University of Tokyo (ISS). I have attempted to share the work of this project with other ISS members through monthly workshops from April onward. Although ISS members specialize in political science, law, economics, and sociology, most of their research themes are related to "Crisis Response" in at least some sense. Therefore, I would say that Crisis Response Studies is an appropriate theme for the ISS.

Fifteen years have passed since I received tenure here at the ISS. For a while, the project in which I was most deeply engaged was "Social Sciences for Hope (Hope Studies)" (2005-2009). Even now many people remain interested in Hope Studies. I am sometimes asked, "What are you doing (as part of Hope Study Project) lately?" or "Do you sometimes visit Kamaishi (as a fieldwork for Hope Study Project)?" The ISS has continued Hope Studies to the present and have updated the "Hope Study Project" Webpage regarding their recent activities.

After beginning the Crisis Response Studies project, I was often asked, "Do you no longer wish to continue Hope Studies?" To this I would answer, Hope Studies in some ways naturally leads to an interest in Crisis Response Studies. When thinking about hope in the future, I feel it is not realistic to assume a situation where there is no anxiety and worry. Even if we are talking about natural disasters or accidents caused by human error, we need to imagine the future as a place where crisis will happen repeatedly. In this future, the prospect that we are able to cope with crisis, or that we are able to get a good response out of our effort, is itself a source of hope for the future. Learning about how to respond to crisis in our society means thinking hope in our society. We have started Crisis Response Studies, but we will not stop Hope Studies!

I was also sometimes asked, "Is Crisis Response Studies the same as Risk Management theory?" Although Crisis Response Studies should humbly learn a lot from existing Risk Management theory, I believe that Crisis Response Studies must somehow strike out in a different direction. Isn't a real crisis much beyond management? However, even if it is hard for us to manage an unforeseen crisis, I believe that we can flexibly respond to that crisis. I want to start to think about crisis response in this sense. The word "crisis (kiki 危機)" in Japanese is composed of the two characters. Interestingly, while the first "ki" means "risk," the second one means "opportunity." In this sense, crisis response involves not only avoiding and minimizing the crisis but also the chance to create new opportunities.

It is my intention to approach Crisis Response Studies in a deliberate way for the next four years.

Starting from Okinawa

Crisis Response Studies aim to be a new type of social science. Having said that, in a manner similar to Hope Studies, when trying to start something new, it can be difficult to get it right on the first try. If we are careless, we might get off track. We need to determine what is important. There are the two important things: 1) paying attention to history, and 2) trying to see the world where we live.

Meridian 180 is an international community composed of about 650 members, including professors, practitioners, policy makers and so on, in various fields across the Asia-Pacific region. This project was launched in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster by Professor Annalise Riles (Cornell University), who was one of the collaborators of our Hope Study Project. Meridian 180 has hosted international conferences in the United States, China and Korea, focusing on issues ranging from democratic countries' aging population to the role of central banks. Through it all, Meridian 180 has pursued two ideals: 1) enhancing transpacific dialogue to find novel solutions, and 2) pooling expertise across professional domains to deal with issues facing the Asia-Pacific region.

The first annual Meridian 180 conference in 2016, "Developing Proposals for Risk Mitigation in the Asia-Pacific Region," was held in Okinawa from July 8 throughout July 10. I was involved in the planning. Although this conference mainly focused on risk mitigation, I believe that the findings which we gathered from intellectuals all over the world are surely impactful on Crisis Response Studies. From the ISS, Shin Arita, Ito Asei, Shigeki Uno, Jackie Steele, Naofumi Nakamura, Takeshi Fujitani, Hiroshi Hoshiro, Kenneth McElwain and myself attended. A typhoon hit Okinawa the day before the conference was scheduled to begin and at one point the meeting seemed like it might be impossible. Yet, in the end, all of the nearly 60 members (saving one member from Taiwan) came together in Itoman as planned.

First of all, I was relieved! Sometimes crisis response means saying a prayer for good luck!

Sharing Our Images

Meridian 180 is a virtual community using the Internet, and we normally communicate with each other by using an e-mail list. Therefore, most of the attendees at the conference were meeting with each other directly for the first time. We all live in different countries and regions. The attendees' professional expertise and experience are also very different. I wondered if it would be possible to discuss 'crisis' within them, given the abstract nature of the theme.

At the conference, in addition to responses toward the risks of natural disasters and geopolitics, we also discussed the possibility of unknown crises. In other words, we discussed a type of risk for which we lacked a common understanding. Before the conference, we asked the attendees to think about how we might develop the capacity to recognize and appropriately respond to an unknown crisis. This idea was "easy to suggest, but hard to carry out." We were left with some uncertainty. What should we do?

In light of this difficulty, in advance of the conference I asked all the attendees to imagine and provide "snapshots" of the next crisis. We requested that every attendee immediately submits a photo and no more than two sentences capturing what the next crisis might look to them. "What most concerns you?" we asked, "What do you see as the next crisis arising in the world you inhabit and work in?"

"What is the next crisis for you?" It might sound like singing my own praises, but I believe that our 'assignment' was successful. Even though it is difficult to develop a shared understanding of unforeseen crisis with words alone, we found that it was possible to stimulate our imaginations with pictures. With the pictures, it is very easy to pose questions and clarify our own problems for the rest of the group. After introducing each attendee's snapshot to the rest of the table, each group projected their images on the presentation screen and opened up discussion with the entire assembly. Given this experience, I think it is important for crisis response to share images as well as words!

My snapshot was taken from a picture book Tsunami Den Den Ko, Hashire Uee (Respond to Tsunami Individually. Run Uphill!) (Text: Kazu Sashida, Picture: Hideo Ito, Poplar Publication) and added to it the following.

According to the book, all students could save themselves from a tsunami by following three disciplines: "Don't stick to assumptions!" "Do all you can!" and "Be the first to act!"

This is the type of response to crisis I would wish for children over the world, so that they might respond to all manner of natural disasters, including tsunami.

The picture, "Boiling a Frog," which Professor Uno introduced, stimulated much discussion. Uno added the text, "We are like a frog in a boiling water. The most serious crisis is the fact that we are too accustomed to crises." The biggest crisis is that we have become accustomed to discourses of crisis. I think that this is a very important point.

I definitely want to try this technique of introducing central themes via snapshots again.

Here McElwain is introducing his group's discussion, presenting their snapshots. He helped livened up the conference atmosphere.

Talk and Action

Some might imagine that an international conference has to be an event where attendees are canned up in the hotel and engage in an endless stream of meetings for two or three days. And, in fact, this is the reality of almost all international conferences. Of course, sometimes conference attendees may join a sightseeing tour on the last day, but only attendees who signed up for the tour could go out.

In contrast, at this Okinawa conference, in the midst of the second day, all the attendees went out to Okinawa to carry out fieldworks for one of the workshops. The workshop title was "Talking to Strangers." All the attendees were divided into groups. They walked around Kokusai-Dori (International Street), a famous sightseeing location in Naha, the former Navy Underground Headquarters reaming war memory, the Peace Memorial Park, the local fish market, and the outlet mall. Everyone had the chance to glance at local people's ordinary lives and talk with strangers (each group was accompanied by a Japanese speaker). Some attendees asked strangers directly what a "crisis" is for them. Other attendees asked them what they felt a crisis might be in the context of their daily lives. I believe that the attendees who came from the outside of Japan felt that Okinawa is probably the most important location in Japan to think about crisis.

The idea of unknown crisis sometimes involves a sense of "estrangement." Similarly, when we try to talk with strangers, we often feel a certain tension and confusion. How we are able to respond to crisis depends a great deal upon how we can involve ourselves with strangers. I believe that the fieldwork activity, which was entitled, "Talking with Strangers," forced many attendees recognize this fact.

After coming back to the hotel from the fieldwork, we did not immediately restart the conference. Instead we began the "Human Sculpture" project coordinated by Professor Riles. Briefly, the goal of this project was for each group to express what attendees felt in the fieldwork by using their own bodies. The important point was that attendees were not allowed to use any words at all. They had to represent what they felt (in terms of risks, crises, etc.) only through actions and the combinations of their own bodies. Audiences were free to imagine and interpret the human sculptures using words. That being said, figuring out the "correct" interpretation was not point.

For someone who is not familiar with this kind of physical expression, this practice can be a little embarrassing. This can be especially true "intellectuals (?)," such as university professors. However, Professor Riles' wonderful facilitation allowed attendees to participate without any hesitation. Everyone enjoyed the project and there was a lot of laughter. I have never attended an international conference with so much laughter! By this point, regional and professional differences had vanished and the attendees began to express themselves freely.

The best way to understand each other is "to try to do something together." That's all there is to it.

Some attendees are watching as others try to make a "human sculpture." Most of them had only just met for the first time the day before.

Plans and Step-by-Step Response

In the last two chapters, I depicted the measures of crisis response as much as not to rely on words such as snapshots or human sculptures. Yet, understanding crisis through the use of words is absolutely essential if we want to recognize and cope with a crisis together. For this reason, the next workshop was entitled "Developing Proposals for Risk Mitigation" and focused on expressing the insights garnered from the previous workshops by using words. In so doing, we adopted the so-called "KJ (Kawakita Jiro method)" method1.

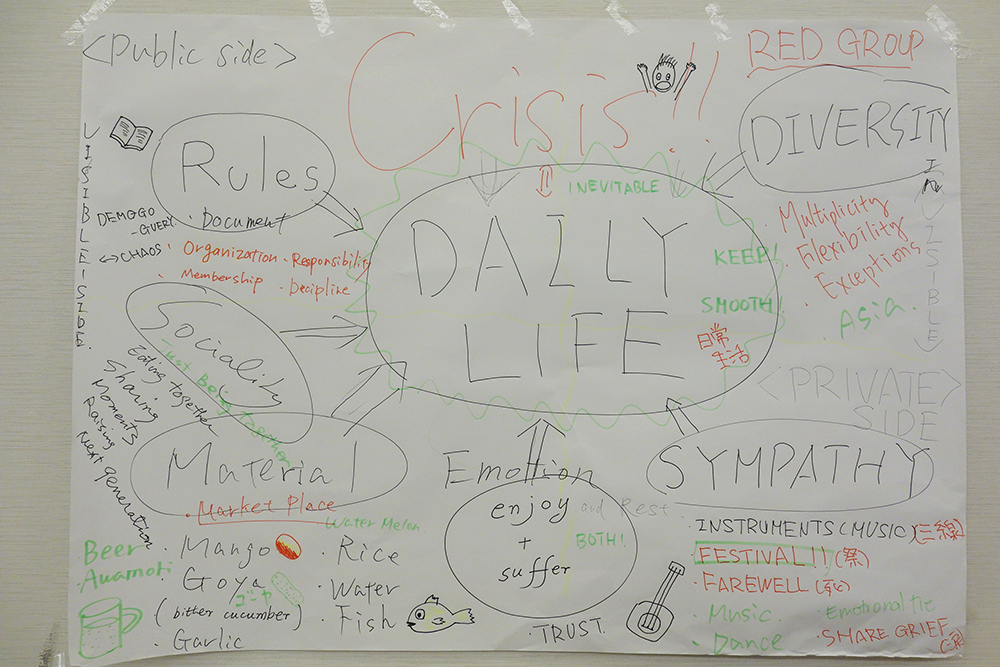

The same groups that went out together and tried to create human sculptures met for this workshop as well. On each group table there were a large amount of post-it notes, some colorful pens, and a piece of large craft paper. The attendees randomly wrote some keywords on the post-it notes. These keywords were what they regarded to be the most important things involved in coping with unforeseen crisis. As they were writing the keywords, they stuck the post-it notes up on the large craft paper. The important point here was to write as much as possible on these post-it notes and not to deny what another attendee wanted to contribute.

After the craft paper had been filled up with post-it notes to some extent, each group started to discuss and change the positions so as to group different words together. Throughout this process, if they thought words were missing, they added new post-it notes to fill the conceptual gaps. At the same time, they began writing some 'meta-keywords' on each craft paper which they felt expressed the common theme underlying the post-it note words. They also added supplementary words, lines, and illustrations to connect the meta-keywords. In this way, each group came up with its own "story." Some of the participants seemed to be familiar with this kind of word and concept association method. Others seemed less familiar. Nevertheless, most of the attendees seemed to be enjoying the collaborative aspect of the project.

Each of the groups suggested unique plans. One group classified a number of keywords, and derived from this a five-step plan as a response in the wake of crisis. The first stage of this crisis protocol was to "recognize" the fact that the crisis has happened (or is happening). In the aftermath of this recognition, people naturally "react" to the crisis with emotions such as fear and anger. However, people then "respond" to the crisis by trying to deal with the crisis in a personal, subjective way. Following this response, they try to "change" their existing situation into a better direction. Finally, while looking back their entire experience of the crisis, they can "renew" their situation.

This five-step plan for crisis response reminded me of E. Kübler-Ross's "The Five Stages of Grief"2. Based on his dialogues with a large number of terminally ill patients, he distilled five stages in the grieving process: "denial," "anger," "bargaining," "depression" and "acceptance." He called "hope" the common feature of the feelings which tend to emerge after the "anger" stage. In connection to this model, does "hope" also come to be a key in response to crisis? This kind of question has clear connections with Hopology. Or, should we find another stage, another key to the crisis problem? For me, one important challenge for Crisis Response Studies is to look the motive power that runs throughout all the various stages of crisis response.

A plan for crisis response. If you look at it carefully, you can find the keyword festival suggested by Professor Ito.

Improvisation and Daily Life

On the last day of the conference, many of the attendees were busy writing essays after breakfast, camping out in their rooms until the very last minute before check-out. This is because each attendee was required to submit a written piece on what they had been thinking throughout this conference. They had to write around 200 words (in Japanese, Chinese, Korean, or English) by 10 am, then submits via email. It was a pretty tightly scheduled conference!

As a member of the ISS, Professor Arita said that "when trying to talk with and understand strangers who have completely different ideas and orientations from us, we sometimes have to approach uncomfortable experiences as a personal responsibility." This insight came from his own "Talking to Strangers" fieldwork experience. With reference to the history of Okinawa, Professor Nakamura wrote,

Nobody thinks someone can change the existing situation. Crisis will take advantage of someone's negligence. It is no use crying over spilt milk. How many times we have heard this proverb?"

Other members of the ISS also wrote unique essays which reflected their personalities. For example, Professor Steele wrote, "Critical 'outside the box' thinking can point us towards the democratic exchanges, tools and processes that will be key to future practices of 'crisis-overcoming"; and Professor Ito wrote, "There is no outsider in the festival." All of the essays sent by the attendees were immediately printed out and posted on the wall of the conference room. After looking for new keywords again, the attendees organized them and discussed the future plans based on these essays. This was the conclusion of the Okinawa conference.

In the last discussion, someone pointed out the importance of improvisation as a new keyword with regard to crisis response (Improvisation means "Sokkyo 即興" in Japanese). This concept contrasts with the method that the workshop adopted on the second day, since we had all been so concerned to work out "plans" as a way to prepare for crisis. When we face a crisis, is it helpful for us to deploy protocol, or is it inevitable that we will respond to each crisis on case-by-case, improvisational basis? If both approaches are important, what kind of social conditions would be needed to the best combination of plans and improvisations. Clarifying this issue is one of the challenges for Crisis Response Studies.

After the conference, we started to consider its outcomes and significance. One of the conference's concrete outcomes is the list of keywords we have posted on the website "What is Crisis Response Studies?" Originally, this list was uploaded in June just after the webpage was created, and was based on a questionnaire distributed last year within the ISS. We were able to renew our list based on the discussion at the Okinawa conference (keywords highlighted in yellow are the new ones).

I believe that you can gather what Crisis Response Studies is going to address through the list. In the future, we will take advantage of a number of productions created at the Okinawa conference such as the snapshots, plans, and the 200-word texts in order to develop Crisis Response Studies as we move forward.

Finally, I would like to close this essay with my 200-word text.

I introduced a page from a picture book on the child survivors of the 3.11 tsunami disaster as my snapshot for the Okinawa conference. The children adhered to the three simple principles: "Don't stick to assumptions!" "Do all you can!" and "Be the first to act!"

Through the conference, I realized that what is needed to cope with a crisis is a set of principles in our everyday lives, that is, in the situation where an unforeseen crisis may occur.

I think that the important thing to develop in our everyday lives is "to have some tools and habits in order to presume the future," "to ensure room for play in order to avoid exhaustion" and "to help people who are trying to act." The way we should respond to crisis in daily life and the type of crisis response during a crisis are exact opposites. For this reason, we can respond to crisis by adopting an opposite method in our daily lives.