Using Constitutional Data to Understand "State of Emergency" Provisions

The Constitution of Japan (COJ), ratified in 1946, is the oldest unamended constitution in the world, but it has been targeted for revision repeatedly by conservative theorists and political actors.1 This essay looks at a new addition to this debate: the insertion of "state of emergency" provisions, which is not explicitly addressed in the current COJ.

Unlike long-debated topics such as the Article 9 "Peace Clause", the political focus on emergency provisions is a recent one. It does not, for example, appear in the 2005 constitutional proposal of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party. However, in the "Question and Answer" appendix to its 2012 constitutional draft, the LDP writes, "Based on the mistakes made and lessons learned from the government's handling of the Great East Japan Earthquake, we decided to specify a clear mechanism for responding to national emergencies."2 Hirofumi Shimomura, Special Assistant to the President of the LDP, stated in a 2016 interview that "Our [amendment] priorities are state of emergency provisions, and then topics that were difficult to imagine 70 years ago, such as environment rights and fiscal discipline" (Asahi Shimbun, May 3rd 2016).3 This statement echoes the preferences of his colleagues. In the 2014 University of Tokyo - Asahi Survey (UTAS) of political candidates, 50% of LDP election candidates for the House of Representatives listed "state of emergency" as one of their Top 3 constitutional amendment priorities, only slightly less than the 58% who listed Article 9.4

What is the purpose of emergency provisions, and how common are they around the world? In the remaining sections, I examine the LDP's 2012 constitutional proposal, which adds two new articles on the procedures (Art 98) and effects (Art 99) of declaring states of emergency, and compare its contents to 186 contemporary constitutions around the world.

Theorizing "States of Emergency"

Nobody doubts that governments should be prepared for extraordinary emergencies, such as natural disasters and international conflicts. In fact, most countries have laws that clarify administrative responses to such crises. In Japan, these are established in the Disaster Countermeasure Basic Act(災害対策基本法), which defines how national and local public entities should utilize public resources to protect lives and property, and the various "Contingency Laws"(有事法制), which outline when and how the Self-Defense Force can be mobilized to protect Japanese citizens and territory. Because crises vary in their foreseeability, escalation speed, and short- vs. long-term magnitude, preparations and responses tend to be enshrined in normal laws, which allow for more adaptability to changing circumstances.

The provision of a "state of emergency" in constitutions, by contrast, is a more drastic affair. Also known as "national emergency provisions"(国家緊急権), its purpose is to create an "exception" to the constitutional regime(立憲主義体制).

In the most general sense, constitutions specify two things. First, they list civil rights and liberties that constrain the government from intervention or discrimination in private affairs. Second, they outline the system of governance, particularly the political institutions pertaining to the selection, survival, and authority of political representatives. Constitutions can vary in their level of detail: for example, the COJ is a relatively sparse document, counting fewer than 5000 words, while the Indian constitution stretches to almost 150,000. However, in a constitutional democracy, specified rights and institutions cannot be abrogated without a formal constitutional amendment. As written in Article 98 of the COJ, "This Constitution shall be the supreme law of the nation and no law, ordinance, imperial rescript of other act of government, or part thereof, contrary to the provisions hereof, shall have legal force or validity."

"State of emergency" provisions grant specific state organs—typically the executive branch—a temporary expansion of powers beyond the regular constitutional framework. For example, the head of government may be allowed to declare martial law, limiting the right to assembly; issue ordinances that have the same force as ordinary law, usurping the authority of the legislature; limit the disclosure of government information, restricting media freedom. These actions are legitimized only insofar as "emergency measures" are necessary to restore regular order and safeguard the lives of citizens.

History offers many reasons to be cautious about national emergency provisions, as they are ripe for abuse. Perhaps the best-known case is Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, which allowed the President to issue emergency decrees without prior consent of the legislature and temporarily curtail constitutional rights. The abuse of these emergency decrees by successive Weimar presidents in the early 1930s generated public dissatisfaction with constitutional democracy, arguably leading to the rise of the Nazis and the demise of parliamentary governance in pre-WWII Germany.5 Similar problems arose in Latin America through the 1980s, where presidents—backed by the military—abused "states of emergency" to legitimize the centralization of power and restriction of civil rights.6

As a result, while most constitutions today specify provisions for national emergencies, they are also more likely to enumerate specific circumstances which count as an emergency, who decides whether those circumstances have manifested, what body exercises emergency powers, and how much human rights can be restricted.

Examining "State of Emergency" Provisions Using Constitutional Data

How common are state of emergency provisions in constitutions? While many scholars look to specific historical comparisons—such as the Weimar Constitution—for inspiration, my work takes a broader approach. Specifically, I use data from the "Comparative Constitutions Project", which codes the content of approximately 900 constitutions, dating back to 1789, on 800 variables.7 This dataset allows us to directly compare or measure trends in the constitutional specification of human rights, political institutions, civil-military relations, and, of course, states of emergency.

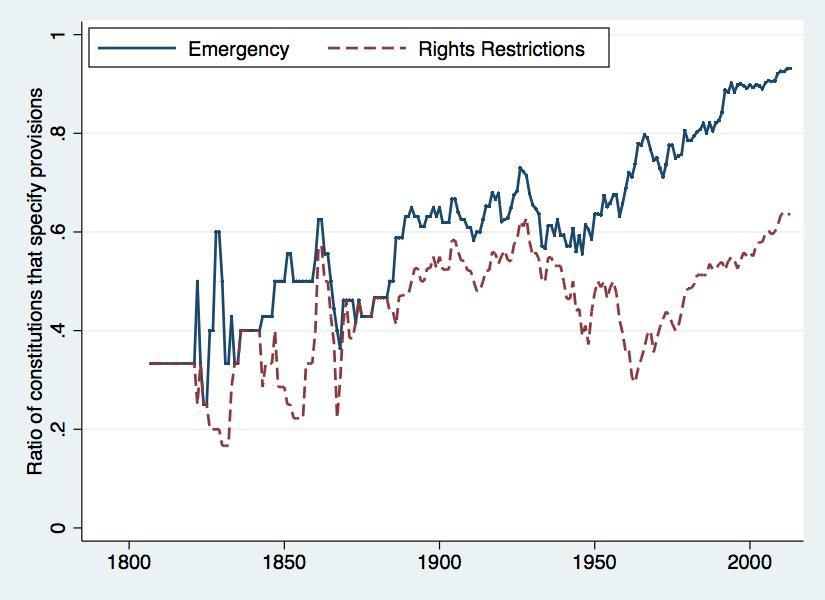

Let me begin with an example. Figure 1 shows the proportion of national constitutions each year that 1) includes any provision for states of emergency (solid line), and 2) allows for the suspension or restriction of rights during emergencies (dashed line). We can see, first, that 90.3% of constitutions today allow for states of emergency, making it one of the more common constitutional topics. By comparison, the freedom of expression is specified in 95.9% of constitutions today. However, the trend for the suspension of rights looks quite different. While the two lines moved in parallel for most of history, there is a major disjuncture in the 1960s. The causal relationship requires further exploration, but only 61.3% of constitutions today permit restrictions of human rights. In other words, constitution-writers are increasingly cautious about delegating too much authority to political elites.

We can also look at more specific elements of emergency provisions. Table 1 lists whether issues pertaining to the declaration and effects of a "state of emergency" are mentioned in the 2012 LDP Draft and in 186 contemporary constitutions.

| LDP 2012 | Global Average | |

| Who can declare? | ||

| Head of Government | O | 66.1 |

| Legislature | 4.8 | |

| Who must approve? | ||

| None necessary | 17.7 | |

| Legislature—both branches | O | 18.3 |

| Legislature—lower house only | 35.5 | |

| Left to non—constitutional law | 1.1 | |

| Conditions for declaring emergencies | ||

| War / aggression | O | 57.5 |

| Internal security | O | 41.4 |

| National disaster | O | 36.0 |

| Left to non-constitutional law | O | 6.5 |

| Effects of declaration | ||

| Non-dismissal of legislature (extension of legislative term) |

O | 18.8 |

| All necessary measures can be taken | 7.5 | |

| Head of State can issue emergency decrees | O | 6.5 |

| Left to non-constitutional law | 4.8 |

The data suggests at first glance that the 2012 LDP draft is not atypical.8 It gives the Prime Minister the power to declare emergencies (also in 66% of contemporary constitutions), subject to approval by the Diet (18%). The circumstances are limited to "External, armed attack on our country (58%), disruption of social order due to civil war (41%), large-scale natural disasters such as earthquakes (36%), and other emergency conditions as determined by law (7%)" (LDP Art. 98.1). The declaration is then subject to "Ex ante or ex post approval by the Diet, as determined by law" (LDP Art. 99.2; 18%). During states of emergency, the LDP Draft also notes that the "the Lower House shall not be dissolved" (LDP Art. 99.4; 19%).

Somewhat rarer, during states of emergency, "The Cabinet can issue decrees that have the same force as ordinary legislation, as determined by law" (LDP Art. 99.1; in 7% of contemporary constitutions), and that these decrees require "Ex post authorization by the Diet, as determined by law" (LDP Art. 99.2).

The LDP's constitutional proposal diverts from global trends in two ways. First, many details, such as the conditions for declaring emergency and the timing of Diet approval, are "left to law", meaning they can be established or changed by a simple parliamentary majority. However, national emergency provisions are serious exemptions to constitutional democracy, and as such, require careful delineation and limitation. While other constitutions also allow legislative remedies for unforeseen circumstances, they are quite rare.

Second, the LDP draft allows for the limited abrogation of human rights. Its Article 99.3 writes, "All persons must, as determined by law, follow directives issued by the government and other public organs that are designed to defend the life, health, and property of citizens. Even in this case, Article 14 [equality under the law], Article 18 [physical integrity and liberty], Article 19 [freedom of opinion and conscience], Article 21 [freedom of assembly, association, and expression] and other fundamental human rights must be given the utmost respect."

This level of discretion is uncomfortably broad. Those provisions designated for "utmost respect" pertain to civil liberties, but who determines whether the government's actions are within bounds, and when can they make the determination? Presumably, the Diet must approve such actions, but they can only do so ex post facto. Even then, if the governing party has a legislative majority, how much independent scrutiny of the Cabinet can we expect? This concern is of particular relevance, since Article 99.4 of the LDP Draft requires only the House of Representatives—whose disproportionate electoral system makes it quite easy for one party to secure a majority—to remain in session during states of emergency.

There are two complementary solutions to these problems. First, there should be more explicit limits on Cabinet decrees, instead of leaving the details to ordinary law, and the Diet should be required to review all decrees within a specified time frame. Second, the Supreme Court should also be given discretion to review decrees, either independently or based on petitions. This would be consistent with its powers under the current constitution's Article 81, which writes "The Supreme Court is the court of last resort with power to determine the constitutionality of any law, order, regulation, or official act."

The Legitimacy of Emergency Provisions

While constitutional revisionists often portray "state of emergency" provisions as purely administrative or logistical procedures, their actual purpose is to provide a supra-constitutional "time out" from enshrined human rights and political institutions. While they are quite commonplace in world constitutions, their parameters tend to be written in detail to limit when, how long, and how much the executive branch's authority can be expanded. In that sense, the LDP draft stands out for its vagueness, as seen by the repeated usage of the term "as determined by law" in sections pertaining to the declaration and effects of states of emergency.

There is also the question of whether these provisions have sufficient public support. Amendments to the COJ require two-thirds approval in both houses of the Diet, followed by ratification by a majority of voters in a national referendum. However, support for constitutional revision has been falling in recent years, and the public's interest in emergency provisions has receded since its peak after the Great East Japan Earthquake.9 This may be due in part to arguments by opponents that most emergency issues can be addressed by existing legislation, such as the Disaster Countermeasure Basic Act and other related Contingency Laws. According to questions on this topic in the Yomiuri Shimbun's 2016 constitutionalism survey (March 17th 2016), 52% responded, "Do not amend the Constitution, but establish new laws that clarify the government's obligations and powers," while only 29% replied that constitutional amendment and clarification are necessary.10

The purpose of constitutional amendments is to solve intractable problems that cannot be remedied by normal legislation. Since they alter the Supreme Law that binds every branch of government, amendments should be considered carefully, with an eye towards unforeseen circumstances and effects. Debates over emergency provisions are not as ideological as those over the Peace Clause or the Imperial System, but given its powers to provide exceptions to constitutional democracy, we should take great care to learn from historical cases and comparative texts to discern appropriate checks and balances.